Deer Lake

Ontario

A few years after Confederation, the government of Canada was faced with a bit of a problem. Things to the east were pretty much hammered out and there were sufficient (white) people living there that sovereignty was not contested. To the west, and that would be anything from the new province of Manitoba west to the Pacific Ocean, and north to the Beaufort Sea, the treaties of 1814, 1818, the Oregon Treaty of 1846 and the Pig War of 1859 had cemented the border between Canada and the U.S. But that cement was still wet. There was a very real danger of land being annexed by the States simply because nobody (white) was living there. So the race was on to expand west and firm up the border. The trouble was that the land was very much owned and inhabited by several First Nations.

To counter this problem, the government of the day came up with a series of numbered treaties, eleven in total. These would gradually extend Canada's sovereignty generally west and north, while eliminating any misunderstandings with the indigenous folks and smoothing the way for white settlers and the eventual assimilation of the savages. First stop, Manitoba.

The Anishinabek, Swampy Cree and Anishinaabe people of southern Manitoba became signatories of treaties #1 and #2 in 1871. Signing the other side of the paper was Sir Adams G. Archibald, the lieutenant Governor of Manitoba and the North-West Territories. Written in the text of the treaties were provisions for 160 acres of land per family of five and a yearly annuity of three dollars per person. For these handsome considerations, the First Nations people gave up the bulk of Manitoba to the crown, thereby making it Crown Land. Of course, not part of the agreement was a large chunk of land given the year previous to the Métis in their much better deal, but we'll talk more about that tomorrow. Back to the First Nations signatories, who were assured that there really wasn't any actual change; until "... these lands are needed for use, you will be free to hunt over them, and make all the use of them which you have made in the past." That the lands were required immediately never really came up; no one asked.

Not written into the deal, but understood by the First Nations negotiators, was the promise that vast tracts of land would be set aside for hunting and the new industry of forestry. They also understood that future generations would receive additional lands to the west, and if the reserves were ever found to be too small the government would give them more land. And to sweeten the deal, there was a promise of plows, harrows, clothing and animals to help with the transition from a nomadic hunting lifestyle to a more stationary agriculture sort of a thing. And, as we will revisit another day, schools and schoolmasters.

Now, the thing about the English language was, if you wrote it down and signed it, then that is what you intended to do. If, on the other hand, you just talked about it, then you were simply negotiating. Whereas the thing about Ojibwe, a Central Algonquian language, is that it was primarily a spoken thing with five distinct dialects and a pictographic written language used mostly to preserve sacred teachings. So, for instance, when the Ojibwe south of the border wanted to send a letter to president Polk to complain about broken promises in their treaty negotiations, the letter was a picture drawn on birchbark. The picture showed a catfish, a man, martens and a bear being led by a crane, with lines running from each totem's eyes and hearts to that of the crane, and all of the totems were standing upon a great lake. This was quite clearly showing that the tribes were all of one mind and heart in their denunciation of Polk's treatment of them. If you were Ojibwe. If, on the other hand, you were English, then the picture was some kind of quaint Indian art and you would hang it up in that room you never use. The Ojibwe would have had a similar use for the written versions of Treaties #1 and #2.

So there was a difference in the interpretation of treaties that went way beyond what you would expect in other contract negotiations. The one side considered the piece of paper to be the only agreement; the other put more stock in the discussions. Even ignoring that, the one side considered reserves to be a fixed thing, whereas the other saw them as being more fluid, ebbing and flowing with the buffalo and other seasonal considerations. The one side saw the agreement as a way of partitioning the land for exclusive use; the other saw the agreement as more of an agreement to share, since their sacred relationship with the land meant that they could neither own nor cede it.

As a partial workaround to the backlash caused when the enormity of the culture clash became apparent to the Ojibwe, in 1875 the feds wrote a Memorandum to be attached to Treaties 1 and 2. It raised the stipend to five dollars from three, and granted some bulls, cows, boars, sows, plows, harrows and buggies. But the exact meaning of the two treaties is still being debated. Which brings us to Treaty #3.

While negotiations were underway with the first two treaties, the Canadian Government decided to build a road all the way from Lake Superior to Lake Winnipeg, an ambitious proposal that would open up the interior of the new country. But the land between Fort William and the Red River Colony was owned by the Saulteaux Ojibwe. Realizing that a treaty would be necessary at some point, the engineer in charge, Simon Dawson, recommended that Robert Pither, formerly of the HBC and quite familiar with the Saulteaux people, be sent to establish and maintain friendly relations.

This move turned out to have impeccable timing, as the Métis of the Red River Colony under Louis Riel started a rebellion right around then which threatened Canadian sovereignty just as it was starting to go so well. A military force would have to be sent across Saulteaux land to settle the rebels, and so Pither immediately set about getting an agreement for that. He was joined by Member of Parliament Wemyss M. Simpson, Indian Agent. Together they assured the Saulteaux that the military was just passing through and they also broached the subject of a treaty for the upcoming road. This was June of 1870.

The Saulteaux agreed not to impede the military force, although they wouldn't help in any way, as it seemed there was likely to be some trouble in the Red River Valley with their Métis neighbours. As to that other thing, the road and its treaty, well they had been talking to their Ojibwe neighbours and so they were not entirely naïve about the whole process, and had their position worked out in advance: ten dollars a head, yearly, for as long as the sun shines, rations of pork, tea, tobacco and flour as well, no settlers, this one project only.

While it wasn't really his affair, Sir Archibald in Manitoba considered the Saulteaux requests to be "out of the question". But it was Wemyss' affair, and he considered the requests to be merely "excessive". He countered with twelve dollars per family of five, and strike the wording about the settlers and the exclusivity of the project. So that was it for the 1870 negotiations.

Next year, the twelve dollars a family clause was still in play, but that figure could go up if the family were larger than 5. For this, the indigenous folks would relinquish their claim to the land. They countered with OK, but it's only a right of way for the road, not the land per se. And that was 1871.

Meanwhile, gold and silver were discovered on the land north of the border, while to the south, the Saulteaux in the U.S. had brokered quite the satisfactory deal with their federal government. So the first nations folk this side of the border began making "new and more extravagant demands" of Simpson. He was going to counter by essentially bribing the leaders - $25 annually for a chief and $15 annually for a band leader. But no one showed up for the talks. So that was it for 1872.

The next year there was a bit more urgency to the negotiations. In addition to the road, there were plans to build the Canadian Pacific Railway between Lake Superior and the Red River, and there was still only the one way to go; straight through Saulteaux territory. The southern Saulteaux had accepted their treaty with $14 a head and an annual payment of between $6 and $10, for up to twenty years. So this side of the border the offer was up to $10 a head up front and $5 yearly in perpetuity. Chiefs were to receive $20 per year and, as always, schooling would be provided "so that your children may have the learning of the white man." So as to let the Saulteaux "feel and know that the treaty is a matter of the greatest importance", the negotiating team showed up with a large military escort.

The counter offer, made by Chief Ma-We-Do-Pe-Nais, was $50 per year for chiefs, $20 per year for council members and $10 per year for everyone else. Also there was to be a one-time payment of $15 a head, as well as clothing, tools, equipment, kitchen gadgets, food and animals. And it was stressed that this was not for the ownership of the land, merely its use. On this point alone, the counter offer was refused.

But then the First Nations side crumbled somewhat. Chief Sah-katch-eway and the Lac Seul and English River bands decided to sign on their own. The government took advantage of this development and told the other chiefs that they could sign as a whole, or the negotiations would continue with individual bands. The rest was merely a matter of dickering over the terms, and Treaty #3 was signed on 3rd October 1873. It has suffered over the years from the same issue as the previous treaties - the interpretation of verbal vs. written text, or what you might consider the spirit vs. the letter. The debate continues to this day, but nonetheless, treaty three was a turning point for First Nations leaders and their understanding of how the game was played. And the game was to be played eight more times. But for today's story we're concerned with Treaty #5.

The fifth numbered treaty, the "Winnipeg Treaty" was actually initiated by the First Nations people living around Lake Winnipeg. The fur trade had virtually collapsed; there was an outbreak of smallpox, and starvation was a real possibility, especially for residents around Norway House, thirty or so kilometers north of Lake Winnipeg. So this treaty included provisions for money to help entire bands relocate from the land they were ceding to new reserves which would hopefully be more sustainable.

The original treaty was signed on 20 September 1875 by the Berens River bands, and then proceeded piece-meal for a year and a half, gaining signatures from regional bands rather than a larger body. The first nations were not the only ones to learn from Treaty #3. A year later, most of the bands were signatories, but negotiations and signing would continue with the "adhesions" well into the next century. The last signatories in 1910 were the Oji-Cree people living around Deer Lake, technically just within Ontario, but still within the jurisdiction of Treaty #5.

Deer Lake was a small nation which became an even smaller reserve of just over 4,000 acres, situated around their namesake lake and pretty far removed from anything in any direction. It was this isolation that had kept them out of most dealings with white folks, other than the few who travelled to the HBC outposts at Island Lake or Big Trout Lake to trade in furs. Since Indian names were unpronounceable, the HBC assigned anglo names to those with whom they had dealings; the Pelican clan became Meekis, the Sturgeon and Caribou clans became Rae, and the Sucker clan became Fiddlers. In particular, Zhaawano-giizhigo-gaabaw, he who stands in the southern sky, became Jack Fiddler.

Jack was much more than simply a trapper. His father,

Peemeecheekag, porcupine standing sideways, was something of a shadowy figure who had arrived at Deer Lake from "the east" in the previous century and was adopted into the Sucker clan. There he proved to be both politically and spiritually inclined, and became a respected leader in both spheres amongst all the Oji-Cree clans, and even amongst some Ojibwe. Peemeecheekag passed these qualities on to his son Jack, who, in addition to being a rare fiddle player, a loving husband to five wives and a devoted father to thirteen children, was a powerful shaman who could rid a person of the feared Wendigo.

A Wendigo was a malign spirit, sometimes sent by evil shamans from a warring neighbour, sometimes just spontaneously coming into being. They preyed upon the weak and the sick, the starving and the dying, which was essentially everyone, since most of the animals, and in particular the fur bearing ones, had all disappeared from the boreal forest. A Wendigo would cause its victim to attack, kill and cannibalize others, typically the former loved ones of its victim.

The cure for Wendigo possession was simple. After the necessary rites and ceremonies were carried out, then you killed the body the Wendigo was inhabiting. In some cases, Jack was asked to drive the evil spirits out of very sick loved ones by their families; sometimes it was by the possessed themselves, before they got too sick. In rare cases the Wendigo was too powerful and Jack would have to take the initiative without being asked, as was the case with his own brother on a trading trip in which the food ran out. In all, Jack sent fourteen souls on in peace, and fourteen Wendigos back to hell.

News of Jack's power against the Wendigo was legend, and it was inevitable that it would come to the attention of the North West Mounted Police at some point. The NWMP did not believe in Wendigos. But they did believe in murder. Canada at the time was very much interested in asserting Canadian sovereignty and Canadian law all across the country. So in early 1907, two NWMP officers showed up at the Sucker camp of Deer Lake. They were the first white people most of the Oji-Cree had ever seen. The officers announced that it was forbidden to marry more than one wife, overlooking the fact that the decree would be a death sentence for many women. And then they arrested Jack and his brother for the murder of Jack's daughter-in-law, Wahsakapeequay.

The only witness during the trial, Angus Rae, Jack's brother-in-law, testified that Wahsakapeequay was in unbearable pain and terminally ill at the time of her death. He also testified that this was a mercy killing, and it was all done properly in accordance with the customs of the Oji-Cree. He went on to state that none of the Oji-Cree were aware they were subject to Canadian law at the time, nor what that law might have been. The HBC traders familiar with the case and even the local missionaries pleaded for Jack's release, but nonetheless, he was convicted and sentenced to death.

The appeals continued, and a release was secured for Jack, but unfortunately he had taken his own life three days earlier rather than submit to laws he did not understand. With their spiritual and political leader gone, and the white folk plainly not going away, and disease and starvation the likely outcome of another winter isolated in the bush, the people of Deer Lake signed the adhesion to Treaty Five. But the land was still not capable of supporting everyone, so many left and went to nearby Sandy Lake, including the remaining Fiddlers of Sucker clan. A few other clans left and headed to North Spirit Lake. Scattered across three locations, the entire population of Deer Lake nation numbered around 78 souls.

These days, the diaspora of Sandy Lake and North Spirit Lake have returned, and Deer Lake is a somewhat thriving, though still quite remote, community of 1,100 people living on-reserve, with an additional hundred or so living elsewhere. As signatories to Treaty #5, the people of Deer Lake are entitled to a yearly gift of ammunition, twine for nets, a fine new suit of clothing every three years for chiefs and councillors, and, of course, five dollars for each and every man, woman and child, payable yearly.

They are also collectively the owners of 160 acres of land per family of five, subject to the whims of the federal government and survey crews of 1914. The reserve encompasses 4,086 acres (which does not divide by 160) of stunning wilderness which you can get to in winter by ice road, or, of course, at any time by air. They are a regional hub and so have a fairly nice airport, serviced by four airlines. This last thing will become quite important in the near future, because the people of Deer Lake have just signed a new treaty. This one is with Frontier Lithium, who believe that there are extremely valuable minerals to be had on Deer Lake territory, and also at nearby Sandy Lake. If money has any part to play in it, I believe the Wendigo issue has been solved.

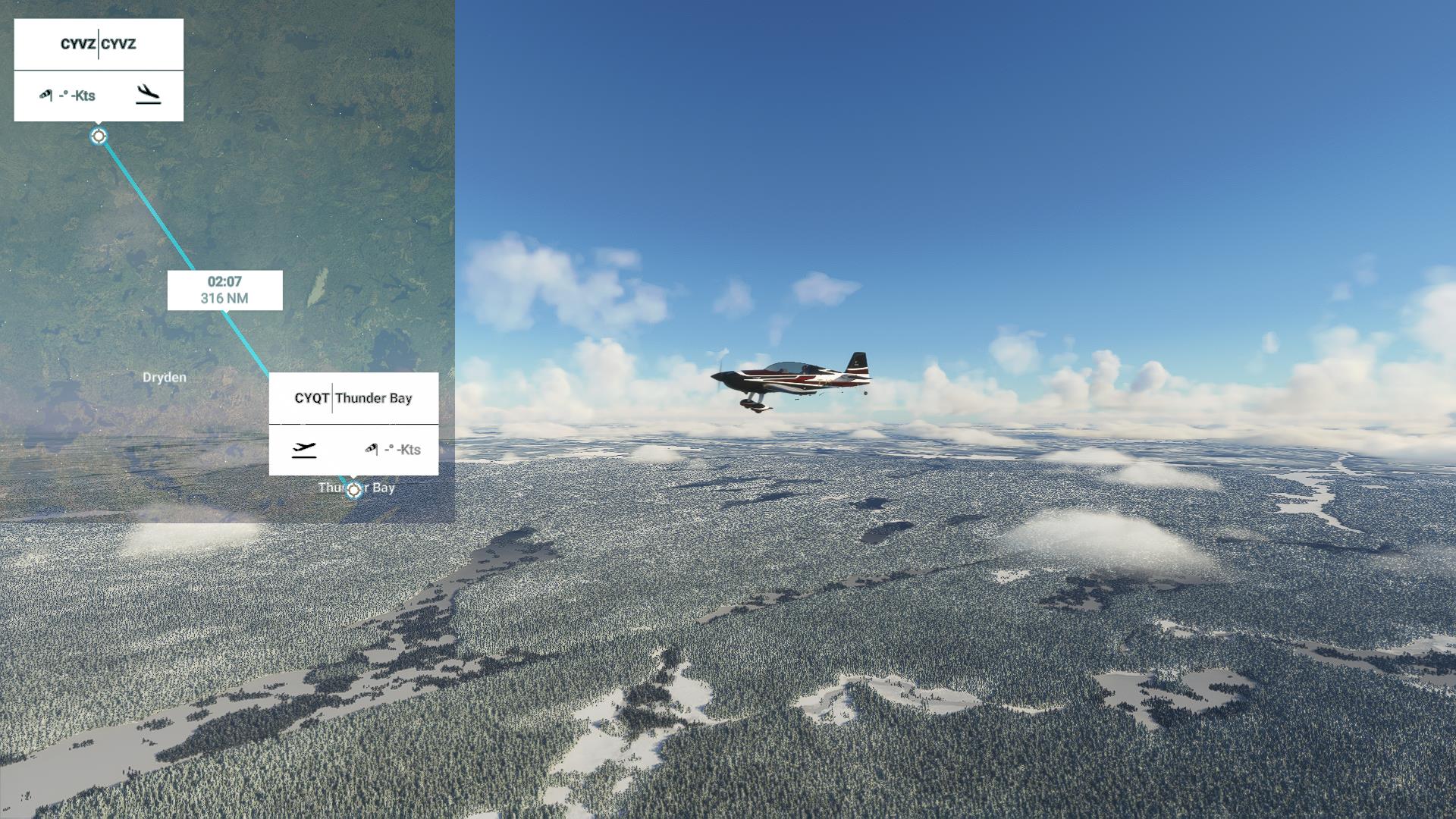

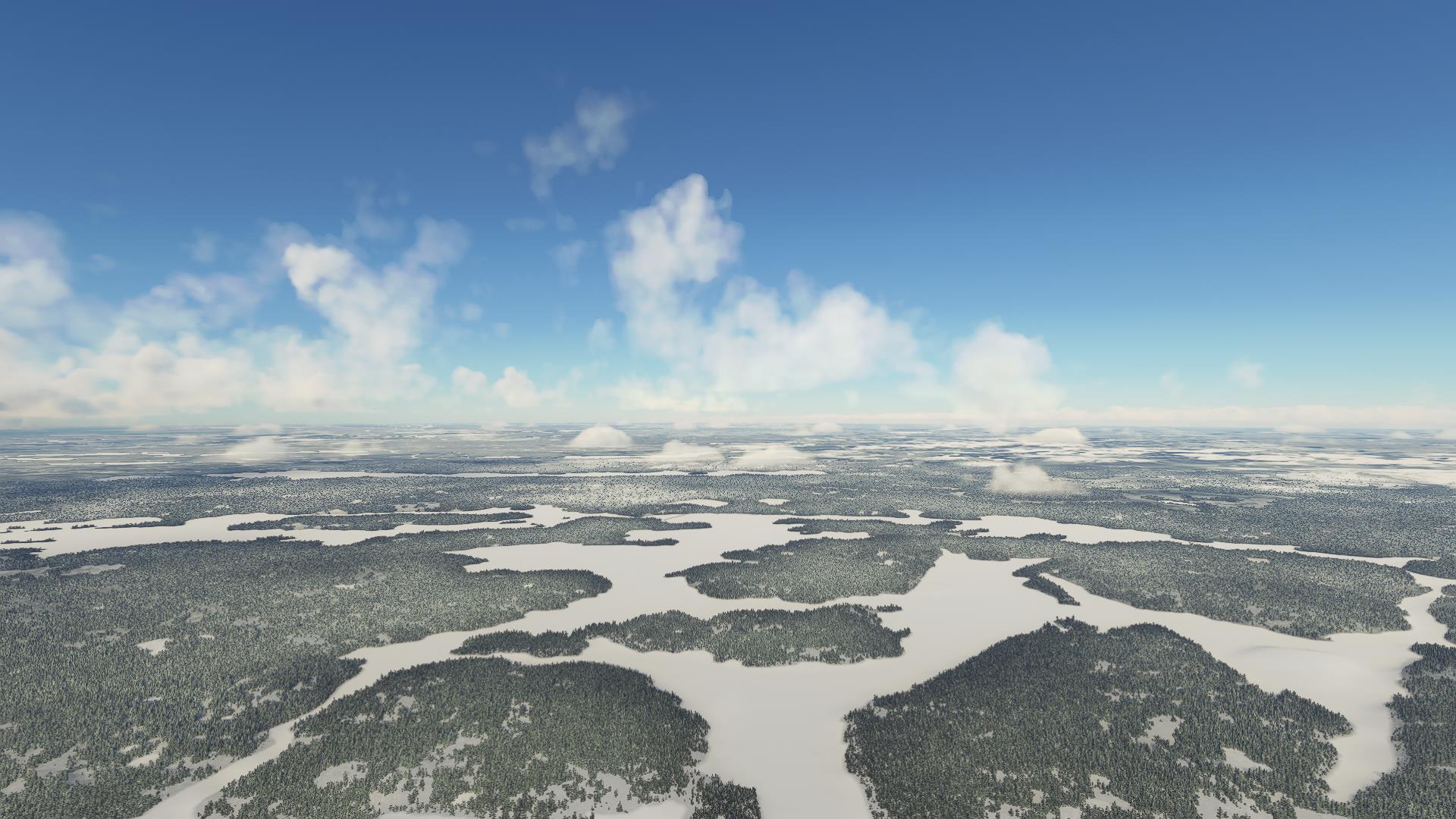

It's pretty remote up here.

It's pretty remote up here.

|

Near Sioux Lookout. This is Ojibwe land, and the Sioux were not welcome. There's a mountain here where one can stand watch for invaders, and it gave the town its name.

Near Sioux Lookout. This is Ojibwe land, and the Sioux were not welcome. There's a mountain here where one can stand watch for invaders, and it gave the town its name.

|

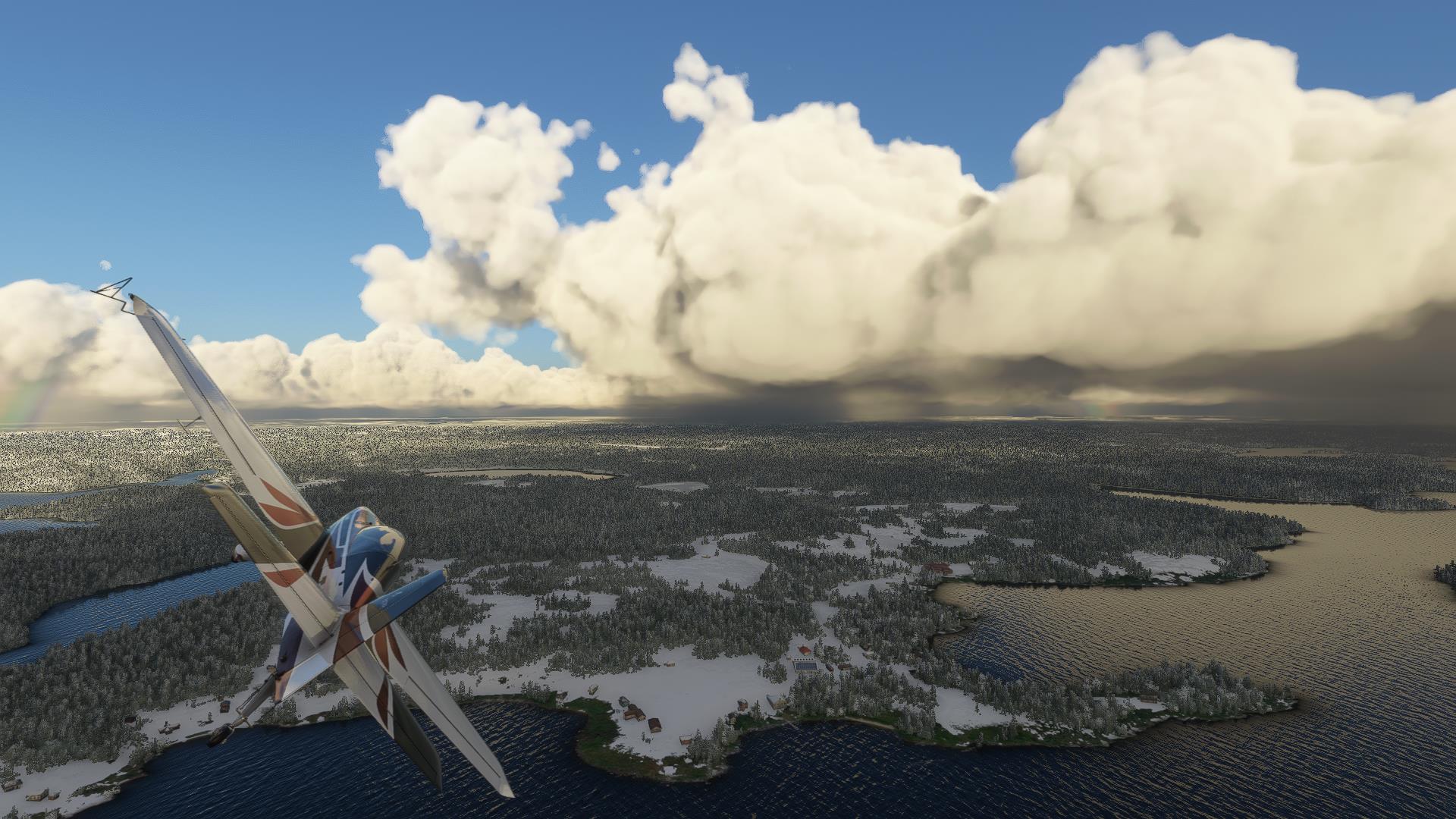

And this is the town of Deer Lake.

And this is the town of Deer Lake.

|

Here we go.

Here we go.

|